It’s not whether you’re right or wrong that’s important, but how much money you make when you’re right and how much you lose when you’re wrong.

This potent philosophy from George Soros captures the essence of what separates good investors from the true masters of the craft. In the world of finance, these masters are known as "superinvestors", a small group of individuals who have consistently and significantly outperformed the market averages over long periods.

The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville

The concept of the "superinvestor" was formally introduced to the world in a 1984 speech by Warren Buffett at Columbia University, later published as an essay titled "The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville." In it, Buffett challenged the prevailing academic theory of the time: the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH). EMH proponents argued that stock market prices reflect all available information, making it impossible to consistently "beat the market" through skill. Any outperformance, they claimed, was purely a matter of luck.

To dismantle this idea, Buffett presented a powerful analogy. Imagine a national coin-flipping contest where 225 million Americans each bet a dollar. After each flip, the losers are eliminated. After 10 flips, about 220,000 people will have correctly called heads ten times in a row. They might write books on their "technique," but we would dismiss it as pure chance. After 20 flips, only 215 winners would remain. At this point, these winners might be hailed as geniuses.

"But," Buffett proposed, "what if a disproportionately large number of the winners—say, 40 out of the 215—all came from one small town in Nebraska?" You would no longer dismiss it as luck. You would travel to that town to find out what they were doing differently.

This was Buffett's masterstroke. He revealed that a group of investors, all of whom had learned from the same intellectual source (Benjamin Graham and David Dodd at Columbia Business School) had produced long-term records that demolished the S&P 500 index. The "small town" was the intellectual village of Graham-and-Doddsville. The investors he cited included Walter Schloss, Tom Knapp, Ed Anderson, and his own Buffett Partnership. Their shared origin and staggering success were not a coincidence; it was proof that a specific, learnable methodology could produce extraordinary results.

While this school of thought produced the first recognized superinvestors, the modern era has seen the rise of new titans who have found entirely different, yet equally successful, paths to outperformance.

What Defines a Superinvestor?

A superinvestor is not just someone who gets rich in the markets. Many fortunes are built on leverage, speculation, or inside access to information. Superinvestors are different:

Consistency across time – They outperform in bull and bear markets alike.

Repeatability of method – They rely on clear, disciplined approaches, not luck or one-off bets.

Long-term focus – Their results are measured in decades, not months.

Clarity of philosophy – They operate with a coherent worldview, often contrarian to prevailing fashions.

Ability to manage risk – They survive downturns, protecting capital while others are ruined.

This combination of traits makes them extremely rare. The financial world is filled with funds that flare brightly for a few years, then fade. The superinvestors endure.

The Archetypes of Mastery

While Graham-and-Doddsville produced the first recognized superinvestors, later generations found entirely different yet equally successful paths. Broadly, they can be grouped into several archetypes:

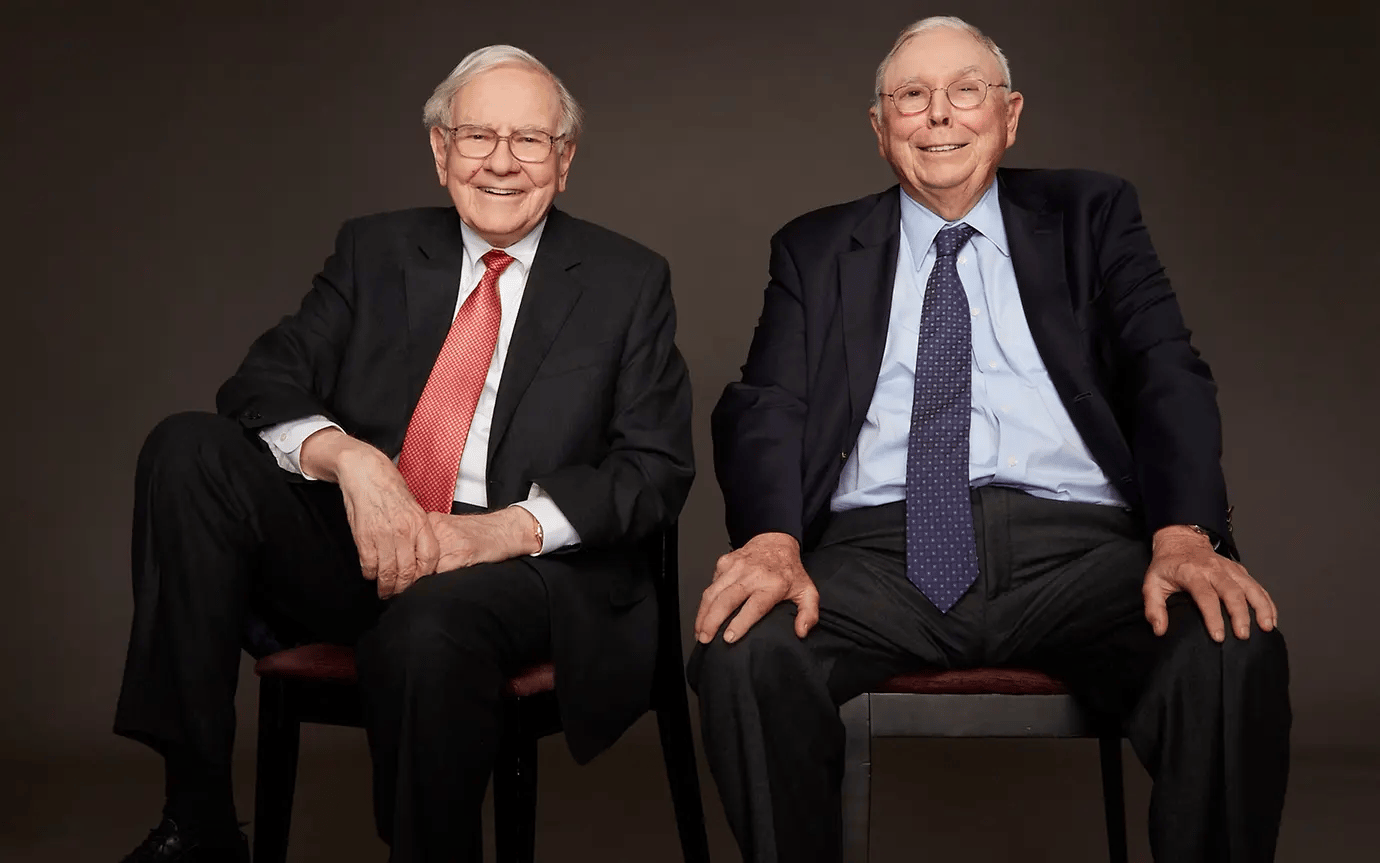

The Quality Value Investor: Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger

Disciples of Benjamin Graham, value investors buy securities priced well below their intrinsic value, demanding a "margin of safety." While Buffett began as a pure “Grahamite,” buying “cigar butts”—mediocre businesses so cheap they offered one last puff of value—he evolved under the influence of Charlie Munger. He realized it was “far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.”

Together, they invested in dominant businesses with durable “economic moats” like Coca-Cola, American Express, and See’s Candies. Their genius lay in spotting these moats, judging their durability, and waiting patiently for Mr. Market to offer a sensible price. By following these principles, Buffett and Munger built Berkshire Hathaway into a trillion-dollar conglomerate.

The Growth Visionary: Peter Lynch

While value investors look for bargains, growth visionaries seek businesses with scalable models and durable competitive advantages that can compound value for years. As manager of Fidelity’s Magellan Fund (1977–1990), Peter Lynch achieved a legendary 29.2% average annual return by popularizing the idea to “invest in what you know.”

He encouraged ordinary people to use their local knowledge to identify promising companies early. Famous for his “scuttlebutt” method—visiting stores and talking to customers—Lynch showed that business-focused analysis could be applied on a massive scale.

The Macro Strategist: Ray Dalio

Macro strategists view markets as interconnected systems influenced by currencies, interest rates, and geopolitics. Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, operates at this 30,000-foot level. He built a framework for understanding “The Economic Machine,” arguing that economies follow timeless cause-and-effect relationships.

His firm systematized decades of historical data to anticipate how debt and business cycles unfold. Dalio is also famous for his culture of “radical truth and transparency” and for pioneering the All Weather Strategy, a portfolio designed to perform in any economic environment.

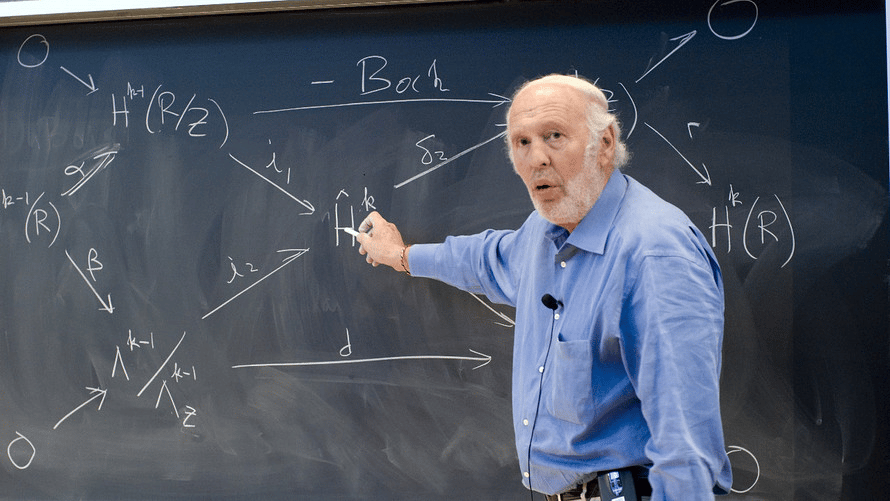

The Quant King: Jim Simons

Not all superinvestors are intuitive stock pickers. Jim Simons, a former mathematician and founder of Renaissance Technologies, epitomizes the quant revolution. His secretive Medallion Fund averaged around 66% annual returns before fees for decades by ignoring balance sheets and P/E ratios.

Instead, his team of scientists built “black box” models to exploit tiny, non-random patterns in vast datasets through millions of automated trades. Simons proved one could conquer the market not by analyzing businesses, but by decoding the market’s own patterns.

The Contrarian Activists: Carl Icahn and Bill Ackman

Carl Icahn and Bill Ackman seek underperforming companies where they can unlock value through activism: pushing for management changes, restructurings, or spin-offs. Their success requires not only financial acumen but also boldness and influence. For instance, Carl Icahn's famous campaign for Apple to return more capital to shareholders ultimately resulted in a massive buyback program that benefited all investors. Their success requires not only financial acumen but also boldness, influence, and a willingness to wage very public battles.

Each archetype shows that there is no single path to superinvestor status. The unifying thread is conviction, discipline, and an edge—whether analytical, psychological, or technological.

What Sets Them Apart?

Looking across these figures, several themes emerge:

Discipline vs. Emotion – Where average investors panic in downturns or chase fads in booms, superinvestors remain calm and opportunistic.

Independent Thinking – They are often contrarian, willing to look wrong in the short run to be right in the long run.

Patience – Buffett famously said, “The stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient.” Superinvestors embody this maxim.

Risk Management – Most are focused on protecting capital as much as growing it.

Learning and Adaptation – Markets evolve, but superinvestors adapt. Buffett shifted from “cigar butts” to quality companies. Dalio codified his principles into repeatable systems.

Can Ordinary Investors Learn from Them?

Are superinvestors unique geniuses, or can their wisdom be applied more broadly? The answer is nuanced.

Replicating Buffett or Simons is nearly impossible. Buffett had access to unique deals, and Simons employed world-class mathematicians. But learning their principles is very possible. Margin of safety, patience, diversification, independent thinking, and emotional discipline apply at any scale.

The key takeaway: don’t try to copy their stock picks. Cultivate their temperament. Emotional control, humility, and consistency matter more than brilliance.

Is the Superinvestor Era Over?

In the 21st century, some argue that the superinvestor's edge has eroded. Information travels at the speed of light, and armies of analysts and powerful algorithms instantly pounce on any perceived mispricing. The simple, statistically cheap stocks that Walter Schloss found are much harder to come by.

While the environment is certainly more competitive, the core principles remain as relevant as ever. Markets are still driven by human emotions of fear and greed, creating periodic opportunities for the rational and patient investor. The rise of passive investing and high-frequency trading may even create more inefficiencies for those willing to do the hard work of fundamental business analysis. The modern superinvestor may need to look in less-trafficked areas of the market: complex spin-offs, post-bankruptcy equities, or smaller international markets. However, the underlying task remains the same: find the gap between price and value.

The Myth and the Reality

It is important not to romanticize superinvestors. Survivorship bias is real: for every Buffett or Simons, there are hundreds who failed. The line between brilliance and recklessness can be thin: see Bill Hwang of Archegos Capital, who imploded spectacularly after years of success.

Yet the myth of superinvestors persists for good reason. They represent hope that skill, insight, and discipline can triumph over randomness. They embody the dream of mastering uncertainty, of seeing further than the crowd.

Lessons for the Future

Superinvestors are not gods. They are human beings with temperaments, philosophies, and disciplines that allowed them to succeed where most fail. Their stories illustrate that while markets may be efficient most of the time, inefficiencies exist for those patient and skilled enough to exploit them.

For the everyday investor, the lessons are clear:

Think long-term.

Avoid emotional decision-making.

Seek a margin of safety.

Be independent, even contrarian when warranted.

Above all, respect risk.

In a world where algorithms scan markets in microseconds and trillions of dollars flow passively into index funds, the era of the superinvestor may seem like a relic. But as long as markets are driven by human psychology, the potential for extraordinary investors to rise above the crowd will endure. Their legacies remind us that investing is not merely about numbers, but about judgment, temperament, and character.